IN SUMMARY

The pandemic brought some garment manufacturing jobs back to the U.S., particularly Los Angeles. But the clothing industry says a bill meant to protect garment workers’ pay could move jobs offshore again.

A bill that would have fundamentally changed how garment workers are paid had enough votes to pass during last year’s legislative session, its supporters say, but ran out of time during the session’s frenzied final hours.

This year, the Garment Worker Protection Act is back as Senate Bill 62, and Sen. Maria Elena Durazo, a Los Angeles Democrat and its sponsor, is on a barnstorming tour across Southern California to gin up support ahead of this year’s session.

“I’m proud to be a Californian,†she told an audience in Venice. “One thing I’m not proud of is the exploitation and the wage theft that’s taking place in Los Angeles day after day after day.â€

But garment manufacturers say the pandemic provided an unexpected boon to their business in the U.S., a nascent success story amid economic calamity that is threatened by the bill, which creates new liabilities across California’s clothing supply chain from factory subcontractors to retailers.

Pandemic supply chain disruption

“This pandemic has created a surge of business back in the U.S.,†said Scott Wilson, president of the Los Angeles organic garment manufacturer UStrive Manufacturing. “The global supply chain disruption has my phone ringing off the hook.

“We don’t need anything right now to hinder that, at all. This is a golden window. And I’m concerned that this bill will cut the knees out from underneath the garment industry here in Southern California.â€

The bill isn’t aimed at manufacturers like UStrive. Instead, it’s targeted at the underground garment industry by forcing them to pay by the hour. Workers in those shops and academics who study the garment industry have told CalMatters that underground operations are able to move among buildings seemingly overnight in order to avoid detection.

While running underground operations, they’re able to pay a rate as low as 12 cents per piece, which garment worker advocates say qualifies as wage theft.

Garment manufacturing in Los Angeles

Los Angeles is the center of apparel manufacturing – indeed, this year, a Vietnamese denim manufacturer opened up shop there. SB 62 would eliminate paying garment workers by the piece, unless they collectively bargain for a per-piece rate. It would also introduce the concept of brand liability to the garment industry, its most controversial aspect.

The brand guarantor provision would extend the liability for wage theft from the factories themselves to the brands and retailers that sell the clothes, as well as any subcontractors in between.

Wilson pays most of his employees hourly, but three of the workers are paid by the piece for higher-skilled garment jobs, and Wilson said they are his three highest-paid employees.

Opponents to the bill, led by the California Chamber of Commerce, have objected most loudly to its liability element. Chamber of Commerce lobbyist Jennifer Barrera said existing law is strong enough to force underground manufacturers to fix their practices or close, if the laws were enforced.

“If you’re trying to get at the root of the problem, which is the garment manufacturers themselves who are already violating California law, that just simply needs to be enforced from our perspective,†Barrera said.

“But if you basically say, hey, anybody up the chain will now be liable for the violations, what incentive does that provide, or what effect does that actually have, on those garment manufacturers to do the right thing?â€

Durazo, the Los Angeles Democrat sponsoring the bill, said in an interview that the manufacturers who don’t break the law are still benefiting from those who do.

“Right now they’re getting the full benefit of contractors who aren’t paying minimum wage because they pay low prices for their clothing and they don’t want to lose that leverage,†Durazo said. “If this was all legit, they could easily take care of the problem. But right now, they get to control it but they don’t have to take responsibility for it.â€

Reshoring clothing manufacturing jobs

The concept of returning manufacturing stateside is called reshoring, a reversal of the trend in the 1980s that sent garment work overseas.

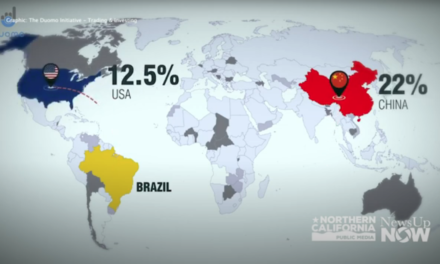

Broadly speaking, the concept of bringing manufacturing back to the U.S. remains a long bet. Leading management consulting firm A.T. Kearney’s Reshoring Index found that disruptions to the global supply chain resulted in wild swings in domestic manufacturing in 2020. Its analysis found more jobs were offshored in the second quarter of last year. That flipped by the third quarter, sending more jobs back to America.

But the net result was still negative. American manufacturing had a lower reshoring index than at the start of 2020. That could be changing. A Kearney survey of 120 U.S. manufacturers found that more than 40% had brought production from overseas back to the U.S., and more than one-fifth had plans to do so in the next three years.

Indeed, after major retailers like J.C. Penny, Brooks Brothers, Pier 1 and Neiman Marcus filed for bankruptcy amid the pandemic, reshoring advocates issued told-you-so missives scolding the multinationals for failing to foresee the collapse of global supply chains.

Not every garment manufacturer agrees with the Chamber. A group of sustainable manufacturers wrote to the Chamber in late July, demanding that SB 62 be removed from its Job Killers list.

“Your designation of SB 62 as a ‘Job Killer’ is offensive given that garment makers in LA lost their lives during COVID-19 precisely because endemic wage theft robbed them of the savings and safety net necessary to stay home from work,†the letter read.

Legislation for garment workers protections also create new liabilities

Producing garments stateside is more expensive, although companies usually don’t spell it out like American Apparel, which caught some flack from the U.S. manufacturing industry for pairing its Made In America line next to the same garments made cheaper overseas.

Wilson said stepped-up enforcement from the Labor Commissioner’s Office can counteract the worst actors, without making major retailers liable – and nervous. He said the reason retailers do business with Southern California garment manufacturers is the speed, the design and the worker expertise of his company – everything but the price.

“When you put any pressure on the existing price and don’t add value, they just continue to make it wherever they make it, like in Mexico or China or India or wherever,†Wilson said. “So it’s ultimately going to do more harm to my 200 employees.â€

This article is part of The California Divide, a collaboration among newsrooms examining income inequality and economic survival in California.

(CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics).